![]()

![]()

![]()

The

Transubstantiation of Tommy Angel | feature article | MAGIC MAGAZINE -

Las Vegas | FEB 2006

The

Transubstantiation of Tommy Angel

By Alan Howard

Both “unredeeming and unredeemable,” Tommy Angel is not your

typical gospel magician. He is a brutal, narcissistic evangelist. Who

is it that has such harsh words for Mr. Angel? None other than his creator,

Jonathan Allen.Tommy Angel is a fictional gospel magician, the central

figure in a contemporary art project that bears his name. British artist

Jonathan Allen inhabits this faux religious performer, bringing him to

life primarily for a continuing series of black-and-white photographs.

His evocative images create a mood of combative faith, juxtaposing the

world of devotional religion with that of performance conjuring.

Allen’s own background lies not only in the visual arts, with five

years of university study in Fine Art, but in the world of magic as well.

Growing up in Surrey, Jonathan first encountered stage magic at the age

of seven. “The first trick I ever witnessed,” he recalls,

“was the sliding Die Box, performed at my school by none other than

the current president of the Magic Circle, Alan Shaxon."

His

other childhood influences were his two grandfathers. One of them had

a hobby of making “miniature fairground models which I helped paint

and assemble in a workshop which was full of trickery.” There, he

came across double-headed coins, loaded dice, and a mirror with a semi-circular

cut-out which Jonathan later discovered “had been an attempt to

recreate The Spider & The Fly illusion as described in Hopkins’

Magic, using my mother as the spider.” Jonathan’s other grandfather,

a research metallurgist, later took up landscape painting. “When

I came across his canvases and brushes in the family attic, a space which

I was already using to devise trick routines, the contents of my conjuring

box and his paint box got mixed up and have remained so, metaphorically,

ever since.”

The dual interests took hold. Allen performed regularly in his teens,

working birthday parties and other informal events. Without the presence

of formal magic schools, his higher education became focused largely on

“the study of the illusionism of painting.” Since that time,

his work as a visual artist has continued to explore the way in which

illusion interweaves with everyday life, and shapes contemporary culture

in often unexpected ways.

A number of years ago, Allen turned his attention to religious belief.

“I realized that gospel magic as we know it in the magic community

had left untouched a vast reservoir of imagery,” he says. “Theatricalised

magic performances (such as the beheading of John the Baptist) were a

part of the European medieval mystery plays well before gospel magic’s

father figure, Rev Charles H.Woolston, began performing his ‘object

lessons’ to Pennsylvanian congregations in the early 1900’s.

Being familiar with both art history and magic history, I sensed that

I could draw the two traditions together to develop a series of photographic

images on the theme of belief. With conflicting religious fundamentalism

reshaping global history, the theme seemed apposite. His performance persona

of “a gospel-magician-losing-his-faith” has grown into the

Tommy Angel character of today. Allen calls it “a visual exploration

of the affinity between the character of the evangelist and that of the

magician, both of which have the capacity to hold an audience in a spell

of enchantment through a careful manipulation of its systems of belief.”

Although conceived photographically, Tommy Angel’s first manifestation

was in the form of a live performance Allen gave in 2002 as part of A

Night of Performance Magic at a small theatre in Sheffield, England. Allen

recalls, “This event was mainly directed towards a performance art

audience and explored the way in which artists had drawn inspiration from,

or referenced the traditions of stage magic.” In that first show,

Allen/Angel levitated a cross, presented D’lites as a stigmata routine,

and pulled Jesus silks out of a church offering bag. His current ten-minute

act opens with him arrogantly striding onstage, pounding a wooden cross

into the palm of his hand like a hammer. After levitating it, he points

the cross at a female plant in the audience, who is drawn onstage and

‘converted’ into his assistant Miss.Direction. Angel then

shoots her with a Bang Gun, which unfurls a banner that reads “Faith.”

A remote-controlled statue of Jesus carrying a cross rolls across the

stage on a small wheeled platform, a glass floats in the air beneath a

bottle pouring communion wine, a bible bursts into flame, and Kevin James’

severed hand illusion is presented as a holy relic.

Commenting on his Tommy Angel show, Jonathan Allen says, “The material

is primarily satirical and gets a strong reaction from audiences who seem

to have no trouble unraveling the Christian and magic content with what

often feels from the stage like a kind of shocked empathy.”

Allen does not perform regularly, and certainly does not make his living

as a gospel magician. Photography is the medium in which Angel primarily

resides. The traditional relationship between performance and photography

is documentary, with the photographer documenting whatever takes place

on stage. Here the relationship is reversed, with Tommy Angel ‘stepping

out’ of the fictional world of Allen’s photographs to perform

live. Allen states, “Tommy Angel blurs the line between fact and

fiction, with the viewer never quite sure of his authenticity. In our

increasingly mediated culture, the idea that this somewhat malevolent

figure might be toying with our perceptions is an additionally suggestive

theme within the artwork itself.”

Allen uses the performances as a form of ‘live drawing,' helping

him to compose the still photographs in the same way a painter might make

studies before committing paint to canvas. “On stage, I sometimes

discover new choreographic gestures and imagery which I then selectively

recreate before the camera,” he says. Allen works closely with another

British photographer Mark Enstone to complete the life-sized photographic

tableaux he exhibits in galleries.

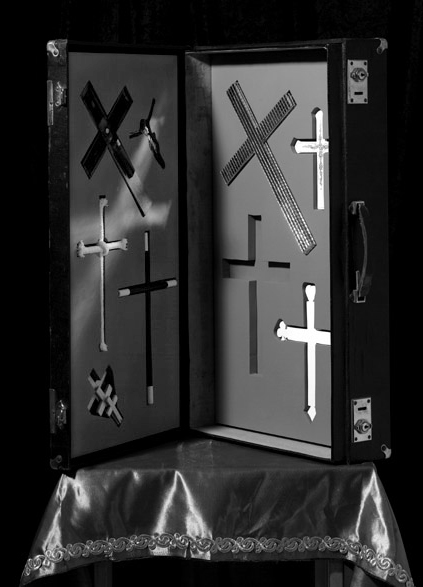

There are routines depicted in the photographs that are not necessarily

portrayed live onstage by Angel. Allen wants his viewers to pick up on

“the associations between the rich iconography of both magic and

Christian history.” To that end, his photos have reinterpreted a

dove act “in a way that reminds the viewer of the many scenes of

Christ’s baptism in Renaissance paintings, when the holy spirit

descended in the form of a white dove.” The traditional black-and-white

magician’s wand has become a cross, just one of many in a suitcase

full of such items, including a rope-cross, a diminishing cross, and a

cross with playing card pips at its ends. The ‘Pharos’ black

art self-decapitation recollects the beheading of John the Baptist, and

a paper-tearing routine — which in others’ hands would read

the word “Hello” — instead reads “Hell”

for Angel.

Allen feels he was probably drawn to the theme of religious belief due

to its strong presence in his childhood. “One of the first details

of magic history that struck me was the theory, often quoted by historians,

that the term ‘hocus pocus’ was derived from a lay mishearing

of the Catholic priests words as he transubstantiates the host, saying

in Latin ‘hoc est corpus’ (‘this is His body’).

Whether true or not, the seeds of the idea that conjuring and religious

belief were somehow connected were planted. You can feel the link by looking

at the word 'conjure' itself, the root of which is in the Latin verb conjurare,

meaning 'to swear together', or 'to form a conspiracy. I delighted in

stories of Catholic monks using wires and ‘engines’ to make

statues blink and cry, in the same way that priests had used stage illusion

technology to impress upon believers in earlier times.

Tommy Angel’s creator/portrayer intends that his acts “put

Christian history on a collision course with the history of magic whilst

at the same time suggesting a subtext about contemporary political culture.

Tommy Angel has been described as Billy Graham meeting David Copperfield

via Donald Rumsfeld.” Allen hopes that such layered meanings are

comprehensible both to viewers of the photographs and to audiences when

he performs live. “My wider message as an artist, and indeed as

a magician, is that the more subtle our expressivity becomes, the more

chance we have of navigating our through the uncertain world which we

seem to be creating for ourselves.”

Allen was one of the moving spirits behind a major art exhibition held

at the Site Gallery in Sheffield in 2002, entitled ‘Con Art’.

He describes the show as “an exploration of the way in which magicians

and visual artists ‘share an imagination’…we wanted

to find out what both communities could learn from one another, both historically

and in terms of contemporary practice.” The show came about after

Jonathan happened to sit next to Amercian art curator Helen Varola at

Monday Night Magic in New York in 1998. Jackie Flosso had encouraged Allen

to attend after Allen photographed him in his Manhattan shop the day before.

Featuring the work of other artists as well as Allen’s own, essays

in the catalogue for “Con Art” were written by, among others,

Eddie Dawes and Jeff Sheridan. The Tommy Angel photographs recently gained

media attention while on display as part of the contemporary art exhibition

“Variety” at the De La Warr Pavilion in the UK last year.

Tommy/Jonathan will be seen in more exhibitions in London this month,

as well as featuring in the first international Singapore Contemporary

Art Biennale this fall.

Allen has remained involved in the magic world outside of his Angelic

endeavors. A chance meeting with illusion designer Paul Kieve more than

six years ago has resulted in several collaborations. In 2004 they worked

together on Carnesky’s GhostTrain, including a version of Pepper’s

Ghost which allowed a performer to dance live with dozens of white doves.

The previous year, Allen assisted Kieve with his work for the film Harry

Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. Other collaborators include British

magician Scott Penrose, with whom Allen performed onstage at the Magic

Circle, as the head in Penrose’s recreation of the Joseph Hartz

presentation of The Sphinx. In 2005, he assisted Penrose again for Dirty

Tricks, “a scurrilous television series recently screened on Britain’s

Channel4 television.” As consultants, both Kieve and Penrose have

contributed to Tommy Angel’s arsenal of evangelical weaponary.

Jonathan Allen has made a serious study of the culture of gospel magic,

more as an artist and sociologist than as an insider. “I do not

share the beliefs or evangelistic ambitions of the community we know as

gospel magicians,” he says. “The images I make are a meditation

on contemporary religious belief set against the political landscape of

our time. I sensed that there might be someone like Tommy Angel out there,

but I couldn’t find him. So I had to become him.”

The artist is committed to increasing magic’s “suggestiveness,”

and to exploring how magic as an art form “ought perhaps recognize

that it is profoundly resonant in a culture that is being increasing shaped

by illusions and fictions of many kinds.

“I have no problem whatsoever with magic being entertaining, and

even light... it’s just when it becomes only entertaining or only

light that I feel it can become culturally trivial.”

Jonathan Allen’s Tommy Angel photographs will be showing at David

Risley Gallery, London Jan12-Feb19. Tommy Angel will perform at Tate Britain

on February 3rd. Jonathan’s work will be featured at the first Singapore

Contemporary Art Biennale, an international exhibition with the theme

of “Belief,” running from September 4 through November 12,

2006."

MAGIC

MAGAZINE >

info

>![]() <

back

<

back