![]()

![]()

![]()

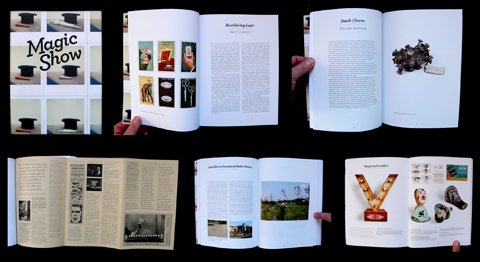

Magic Show, group exhibition | commissioned Hayward Touring exhibition | initiator and co-curator [with Sally O’Reilly] | 2009-10

'Magic Show' was commissioned by Hayward Gallery Touring, co-curated by artist Jonathan Allen and writer Sally O'Reilly, and exhibited at various UK venues between Nov 28th 2009 - Dec 19th 2010: Quad Derby, Grundy Art Gallery, Blackpool, Tullie House, Carlisle, Chapter, Cardiff, and The Pump House Gallery, London.

Magic for some invites the creative agency of fantasy and illusion; for others it signals a licence to practice deception. Curated by Jonathan Allen & Sally O'Reilly, Magic Show considered both these approaches, taking fiction and trickery to be intertwined, historically prevalent and culturally pivotal. The exhibition demonstrated how artists adopt the perception-shifting ploys of the theatrical magician to summon wonderment whilst simultaneously performing critique, but also revealed how strategic illusion and misdirection can be employed in more ominous contexts.

excerpts from Magic Show catalogue:

"The history of art is riddled with perceptual and conceptual games of trickery and subterfuge. Even pictorial perspective is a system of illusion. The demand for truth, whether to materials or an idea, cannot be sustained, because art is essentially grounded in untruth, the fabrication of alternative versions of reality. As a result, many contemporary artists are as fascinated as their predecessors with the theatrical conventions of magic and conjuring, often deploying the devices of the stage performer to subvert habitual assumptions of cause and effect. Vanishing acts, inexplicable transformations and displays of extraordinary psychic prowess are staples of the stage magician, and the artist may play with these same forms of manipulation and mystification, not for entertainment but to reveal something about the fundamental relationship between matter and the mind. How far can the wish for change overcome the inertia of the material world, which so often defeats us and resists our interventions? That this is a political as well as poetic or metaphysical question is one of the implicit themes of Magic Show." [Roger Malbert, Hayward Touring]

"Stage magic does not require audience members to truly believe, but does ask them to hang their scepticism on a peg just outside the auditorium, keeping sharp derision from pricking the bubble of delicious mystification. But where the magician redirects or manipulates credulity to produce temporary, convivial bewilderment in the name of entertainment, the artists in Magic Show employ these strategies for the purposes of reevaluation with varying degrees of gravity, from the gentle prompting of subjective fantasy to political and institutional critique [...] ..by assuming the methodologies of magic, artists too subscribe to a metafiction to power that is ulimately a narrative of bewilderment, instrumentalised to productive, disruptive or controlling ends." [Sally O'Reilly]

"..yet once a ‘natural’, rather than ‘supernatural’, basis for theatrical magic is established, its undoubted ability to radically disorder our epistemological assumptions about the world can be understood in terms of the magician’s capacity to establish and maintain a frame through which simulated power over natural causality is experienced as real. In this sense, therefore, this form of magic is not only secular, but also simulacral. And it is the intentional presence and infinite malleability of this reifying frame, whether in the form of narrative or other contingent means, that brings simulacral magic alongside its sibling arts, and not least the visual arts with which it now shares more conceptual territory than perhaps at any other time." [Jonathan Allen] >

Participating artists: Jonathan Allen, Archive (Chris Kubik & Anne Walsh), Zoë Beloff, Ansuman Biswas & Jem Finer, Joan Brossa, Rick Buckley, Brian Catling, Center for Tactical Magic, Jackie & Denise Chapwoman, Tom Friedman, Brian Griffiths, Colin Guillemet, João Maria Gusmão & Pedro Paiva, Susan Hiller, Alexandra Hopf, Christian Jankowski, Janice Kerbel, Annika Lundgren, Juan Muñoz, Bruce Nauman, Ian Saville, Ariel Schlesinger, Suzanne Treister and Sinta Werner.

Magic Show installation views, Quad, Derby, 2009

Magic Show installation view, Grundy Art Gallery, Blackpool, 2010 [Sinta

Werner, Imperial Measurement, 2010]

Magic Show installation

view, Chapter Art Gallery, Cardiff

Magic Show installation

view, Pump House Gallery, London, 2010

Magic

Show catalogue:

Cornerhouse books [UK]>

DAP

& Artbooks [USA]>

Venues:

Hayward Gallery, Southbank Centre >

Grundy Art Gallery, Blackpool >

Tullie House, Carlisle

Reviews:

Nottingham Visual Arts review >

Art Monthly - see below

Magic Show – Art Monthly issue 335: April 2010

Grundy Art Gallery, Blackpool 13 February to 10 April

In an episode extract from Derren Brown's Trick or Treat, viewable on video at the start of this 24-artist show, art critic Adrian Searle stands with a knife poised before one of three paper-wrapped canvases resting on easels. Ostensibly, he has a one-in-three chance of unknowingly slashing the characteristically grotesque painting Arachnokitty, 2001, by 'Jackie & Denise Chapwoman', which is inside one of them; the artists, better known as Jake & Dinos Chapman, stand watching, smirking, though clearly not entirely sure what to expect. Searle slashes, then removes the paper: phew. He picks another, slashes: right (or wrong) again. Luck? Or had Derren Brown succeeded in a mentalist experiment on the estimable Guardian writer? In the end, it doesn't matter, since one can virtually hear the cogs whirring in the Chapmans' minds before they cajole him into knifing the one sealed canvas left. [The slashed Arachnokitty, retitled When Art Critics Go Bad and dated 2001/06, is on display in the next room.] But if art audiences feel sceptical of Brown's crowd-pleasing powers when compared with the elevated territories they themselves inhabit, it may be partly because there are more parallels between art and magic than we might comfortably admit.

As is intimated by 'Magic Show', co-curated by artist Jonathan Allen [a practising magician and member of The Magic Circle] and critic and curator Sally O'Reilly, both art and magic are concerned with manipulating perception, with the theatrics of suggestion and the leveraging of confidence. Do we really believe that an ii-inch spherical space above Tom Friedman's Untitled [A Curse], 1992, contains a curse placed there by a witch? [Or that the same artist really stared at a piece of paper for a thousand hours?] We try to. The 'it is because I say it is' provocation dates back to Duchamp at least; the charged space of the gallery, which transfigures what it contains, might be analogous to the ritual and razzmatazz of conjuring.

Art, though, as in the Chapmans' wrecked canvas, could be expected to lean more towards puncture than perpetuation; showing the wires rather than making them invisible. Here, it often does. In Juan Munoz's untitled photographs from 1995, we see tiny, cheat-permitting fingertip mirrors on a cardsharp's hands (though the artist was something of a conjuror of atmospheres himself); in Ariel Schlesinger's Netally and I, 2006, a pair of 'bent' pencils were presumably just made that way. In Colin Guillemet's Untitled [anything but a rabbit], 2006--the kind of thing Tommy Cooper might have made if he'd turned to conceptualism rather than comedy--paired Polaroids feature, in the left frame, a carrot beside an upturned top hat; and, in the right, the non-rabbit that has bathetically materialised: a parsnip, a fish, an umbrella. Bruce Nauman's Failing to Levitate, 1966, is a double-exposure photograph which features the artist at once balancing between two chairs and slumped below them; it's an image both unearthly and defeatedly materialist, played with a poker face. Susan Hiller's frieze of photographs featuring people 'levitating', Homage to Yves Klein, 2008, says more about technology than a mystical overcoming of gravity, as does Ansuman Biswas and Jem Finer's Zero Genie, 2001, a video of clownish behaviour on magic carpets, aided by an anti-gravity environment.

And yet we don't live in a fully rational, or at least scientifically comprehended, world: we live in one where, for example, the mind-over-matter rationale of placebos can cure the sick with sugar pills. As is underlined by Zoe Beloffs 3D video playing in a sculptural proscenium, A Modern Case of Possession, 2007--which turns several episodes from the casebooks of early 20th-century psychopathologist Pierre Janet into colourful operetta--the mind gives up its secrets in a slow release from superstition, which looks bizarre in retrospect. Gone are the days when most right-thinking individuals believed in demonic possession, and the illusion of 3D isn't going to shock us anymore (Avatar notwithstanding), but those days aren't so long ago. Plus, there is a pleasure in being fooled, as everything from Derren Brown to this show's historical sidebars of props and posters reminds us. And yet sleight-of-hand infests everything from political spin doctoring to marketing. [Sometimes the linkage is made plain here, as in the tube of Clarks' Shumagic Renovating Polish, nestling in a trans-historical display of magic-related goods, which features a picture of magician Robert Harbin on its packaging.] A selection of archive posters, meanwhile--for 'The Man Who Has Tamed Electricity', or 'The Great Sorcar, World's Greatest Magician' etc--reminds us that 'twas ever thus, and that today's sorcerers will be tomorrow's nostalgic punchlines.

Allen makes one of the show's larger associative leaps when he presents, in Kalanag Double, 2009, a pair of photographs of the masks which Nazi magician Helmut Schreiber, who performed for Hitler himself, used to create an illusion of doppelgangers before live audiences. They are rough-looking things - one assumes they were seen briefly, in shady environments - and they emphatically correlate magic with dangerous levels of deception and shared hypnosis. [A particularly bold move in Blackpool, this.] But perhaps the show's most salient strike comes via Sinta Werner's site-specific installation, which takes features of the Grundy's handsome Edwardian architecture - the columns, the walls - and smashes together fragmented copies of them along with some vertical strips of glass. At first it looks like cubistic chaos, but there's a point where one can stand in which the architecture seems correct, but as if reflected in a pair of sloping mirrors in which a viewer doesn't feature, because they aren't really there. When we angle ourselves and squint and laboriously reposition ourselves to make the illusion real, we're demonstrating what every magician [and not a few artists] pins their act on: the fact that, against the banality of the everyday, we actively want to believe in the magical, because the lie is more exciting than the truth.

Magic

Show tours to Tullie House Museum and Art Gallery, Carlisle, 15 May to

4 July, Chapter, Cardiff, 30 July to 12 September and Pump House Gallery,

London, 6 October to 19 December.

MARTIN HERBERT is a writer based in Tunbridge Wells, Kent.

All works © Jonathan Allen 2012. All photographs are © their respective authors.